The statistics leave little to be desired: only 1 in 4 high-growth companies are led by female founders. What’s more, investments into female-led businesses are declining – receiving just 1.5% of UK investment. At the same time, the gender gap continues to close, with a record-breaking 72.4% of British women in employment in 2019 (vs 78.4% male employment).

This scenario is the same across Europe. Female financial literacy was one of the hot topics presented by Prometeia at Forum Women ONboarding, a UniCredit initiative as part of the UniCredit4Women journey designed to value talent and female growth in the world of banking.

According to Francesco Giordano, Co-CEO Commercial Banking Western Europe at UniCredit, there’s still a huge gap when it comes to female digital entrepreneurship and financial skills. To support women in this area, UniCredit has launched two new initiatives: a female mentoring journey (Women ONboarding) and four Banking Academy financial education journeys. The initiative is part of a wider strategy within the group to protect all forms of diversity and favour inclusion.

Lifeed CEO Riccarda Zezza was part of the panel. The event offered an opportunity to understand how female founders can make all the difference in our post-covid world. In particular, a new generation of entrepreneurs can teach their children to see their finances in a different way. “Women are inherently innovative, offering something different to the status quo on the market, where most businesses are male”, explained Riccarda Zezza.

“Female founders can bring something specific to the table. They can build new paths without having to radically adapt their thoughts or language. It’s important for women to go into business because the world needs a different point of view and new solutions. It’s not about allowing women to run on the same track as the men. Instead, it’s about changing the track to make it more suitable, welcoming the potential of all involved”.

To express their potential, women need to be financially independent. Today, education really makes the difference. But few girls choose to study STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths), as Ersilia Vaudo Scarpetta, astrophysicist and Chief Diversity Officer at the European Space Agency highlighted. “STEM subjects have a great potential to empower women and raise employment figures. They give the highest pay rises and reach gender equality in a shorter time frame”.

According to the World Economic Forum, it will take at least two centuries to bridge the gap between men and women. Italy is way down the Osce gender gap list when it comes to financial knowledge. There are still too few female-led businesses. The ones that do exist are noted for their innovation and social focus.

Scarpetta also emphasised the importance of mentorship for young women. It’s about making space for them to share their experiences and find solutions through their network. It starts with following positive and inclusive leaders. Antonella Mansi, President of the Florentine Centre for Italian Fashion, believes STEM education “is crucial, together with family and scholastic education, ensuring women are ready for the world of business”.

Educating our children on financial independence is incredibly important. Irene Facheris, expert and trainer in gender studies, remembers how her parents taught her to manage her pocket money on an Excel file when she was a child. “Families (and in particular, women) require more financial education”. That’s not all. “School plays its part too, because the pay gap problem starts before we even reach the world of work. We also need to consider that financial violence happens in the family context when managing financial resources”.

The idea of sustainable entrepreneurship, from a human point of view, was highlighted by Lavinia Biagiotti, president and CEO of the Biagiotti Group, who believes “we’re here to leave a legacy for both the environment and people”.

Finally Magda Bianco, Director of the department for client protection and financial education at the Bank of Italy, highlighted the correlation between the level of financial and mathematical competencies. “Schools need to focus on finance, which society often sees as a negative thing. We also need to look at maths in a less competitive and more engaging way. If we can avoid creating stereotypes, we’ll give women more confidence in their own abilities”.

It’s still at the top of the list in the workplace, perhaps now more than ever. We’re talking about diversity and inclusion. So many companies are too young, too old, from too many ethnic backgrounds, too feminist, too new, too *insert difference here* for the system to be able to treat as ‘normal’.

We’re loosing too many, as an army commander would say – or perhaps even a HR director. In reality, we’re loosing too many people because we’re not able to see them for all they really are. We’re trying to transform them into a ‘normal’ that no longer exists. By even trying to normalize people they’re failing one by one: starting with courses to teach women how to look less different, and more similar to traditional power models. It’s how they’ve lost thousands of people. We’ve lost talent because they’ve never had the opportunity to talk with us. We’ve lost those who couldn’t pretend to be the same any longer. It’s as though they’ve had to pretend to be “less” than their whole complexity, when it’s that very diversity that makes our stories and talent unique.

Nobody knew how to say it better than Bozoma Saint John, Chief Marketing Officer at Netflix:

“We hide those broken pieces. Is as if we like to pretend as though they don’t exist. We like to wear the mask, which then is created by somebody somewhere. Somebody said “this is the perfect way to be a leader”. But it’s not true. The ways that we are are important. I’ve lost count of the amount of times in meetings, to benefit this mass idea, we make everything vanilla, losing what is really important”.

Every person’s story counts, says Bozoma in a video filmed for a Harvard Business School course “Anatomy of a badass”: our stories are the only things that really count.

I’m a better executive because I’m an immigrant. And I’m a better executive because I’m a single mother to an 11 year old. I’m a better executive because I’m a widow and because I know how to dance. And I’m always going to say that loud.

It’s always the truth, even when we don’t feel immediately different. We all carry a unique story, we’re always too rich to be boxed off into someone else’s definition. Everybody’s story is cut out when we try to be what other people expect us to be, or rather what we think other people expect.

It’s not an illusion. Stereotypes exist and govern our social and professional lives. It’s natural and instinctive to want to feel like others. Belonging to a collective ground is a precondition to our existence. Being a “badass”, as the famous Harvard course explained, doesn’t mean doing what you want without respecting others. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. It’s the intention to be completely ourselves and that social norms can help us to avoid the chaos: creating shared spaces of expression that make space for authenticity, inclusion and harmony.

Are we pushing beyond the rules that already exist? Not really, because a lot of the definitions that we observe today don’t really reflect us any more, and adapting to them is tiring. This Harvard course highlights that the ability to show our true selves improves our performance and engagement at work. It’s even more true if we can show that we’re different when we feel victims to stereotypes: a type of “anti-fragile” effect where showing our vulnerabilities makes us stronger.

So, what do we need to do? How can we increase inclusion? How can we bring together our individual intensions to strengthen our companies’ efforts to make space for diversity? It’s a hot topic, so much so that I recently took part in a Horasis conference about “We are who we are”, talking to a Greek member of parliament, three American executives and a Bloomberg journalist.

The first step is always the hardest: it’s about our ability to see ourselves for who we really are. What’s remains if we remove other people’s expectations from the mix? It’s not an easy question to answer: it’s a way of looking at ourselves bit by bit, keeping watch on our circumstances and what we do and say, observing what belongs to us and what belongs to the “mask”.

We don’t need to criticize ourselves – we don’t need more guilt! – but we need to see those things, give them a name, be grateful for the security they’ve given us and try to look behind those things. Knowing how to think it natural, and looking behind the mask is a reflective process. So as Harvard teaches us about inclusion, we need to add an organizational component into the mix. The intentional awareness to advance those parts of ourselves, to make them visible in our day to day lives.

Diversity and inclusion in companies or in life touches all of us, not those who are “different”. If a “normal” person did exist in the world, they’d be surrounded by people with rich and expansive stories that couldn’t be contained in other people’s definitions. It would be a representation or a minority, and those special projects would be perfect for them.

This article was originally written by Riccarda Zezza and published on the Il Sole 24 Ore blog, Alley Oop. To read the original article (in Italian), please click here.

Companies often talk about putting “people at the centre” of what they do. It’s an expression we can all agree with. But if it remains simply a slogan, we run the risk of asking superficial questions about our people. That’s where people analytics comes in. Employees are not just professionals: they also bring to work their private lives and transitions that they’re going through.

When we consider this, it’s important for companies to make the switch from Employee experience to Life experience, within the context of caring leadership that considers its people’s diverse identity dimensions. These dimensions may include caregiving roles (being a parent, or caring for elderly or disabled relatives) and other life experiences (changing house or job) that reveal transferable skills that can also be applied at work.

If you want to get to know your employees as people, and not just professionals, you need to working with People Analytics. It’s about considering all of a person’s dimensions to develop tailored growth plans that are more effective.

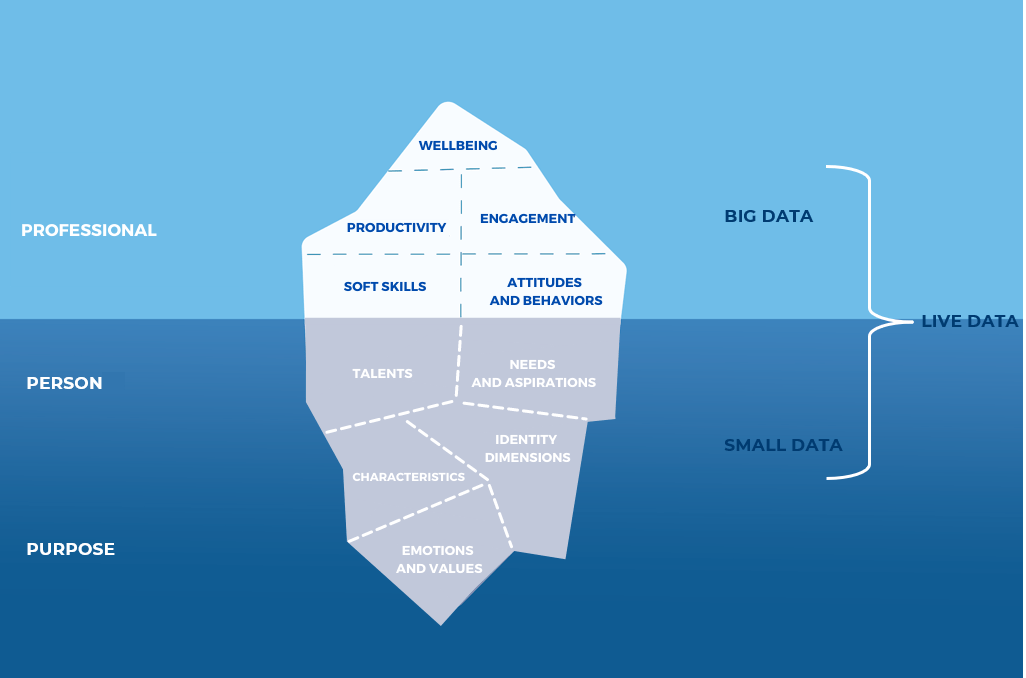

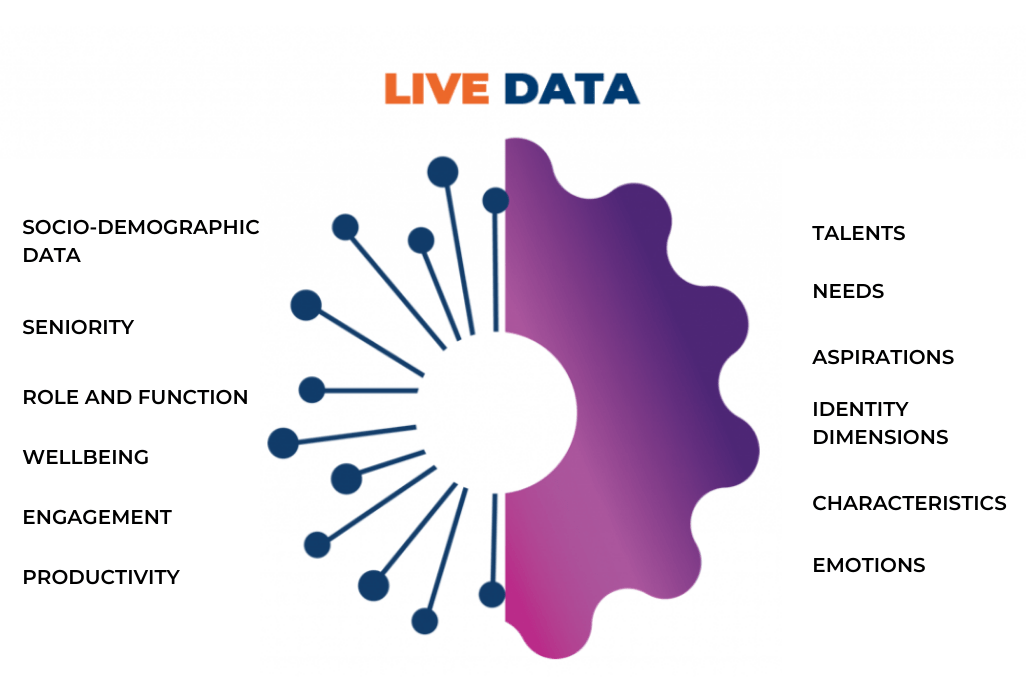

“Companies usually measure elements such as wellbeing levels, engagement and productivity. They tell us ‘what’ we can see of our people at work, but they’re only the tip of the iceberg. Using this metaphor, those elements can be likened to marketing’s Big Data. The ‘why’ looks at the reasons behind the elements that are traditionally measured (and evaluated). We need to look for those in subjective and emotional characteristics, which can be likened to the Small data that Martin Lindstrom talks about“, explains Chiara Bacilieri, Head of Data at Lifeed.

“A combination of Big and Small data creates Live data, a mix that allows HR teams to tailor action plans to their people, to help each individual reach their full potential”, explains Martina Borsato, Data Strategist at Lifeed.

Instead of asking users closed questions, Lifeed’s Life Based Learning method stimulates people’s self-narration. This method reveals emotions, behaviors and skills honed through their current life phases. People can apply these skills at work too.

In this way, people actively create content through reflections on the digital platform. Companies are able to get to know their people better. This allows them to value them for all they are, both in their private and professional lives.

The constant evolution of organizations and corporate culture impact professional development. This generates a new type of leadership. Today, traditional learning methods don’t work for learners. What’s more, they don’t go far enough for managers either. Companies have the opportunity to make the move from “training” to “being”. They are becoming increasingly aware that people’s identity dimensions are resources. Resources rather than obstacles that need to be overcome.

Assessments can touch on the richness of our people. Their lives are complex, with each role strengthening the others. It’s what we discussed at the HRC event The development challenge stems from managerial training, alongside Lifeed CEO Riccarda Zezza.

The HR department has an incredible role in the life of a company. It gives managers the right tools to be able to value their people’s identity dimensions. But “values and purposes must be the living experiences of our leaders, especially when they’re intermediaries”, explained Laura Bruno, Head of HR at Sanofi.

The employee-boss relationship has become increasingly complex, thanks to remote working through the pandemic. HR Directors “can facilitate this relationship. Even if it means encouraging managers to ‘manage’ with courage, kindness and generosity”, says Tiziano Suprani, Corporate HR Officer at Ferroli. To do so, we need both a “stimulus from the employee’s side, or rather a willingness to focus on self-directed learning”. Proactive managers that “know how to guide people’s talents” are also much needed.

It’s not enough to be a coach on the sidelines. We need to move onto the pitch. Today, organizations are fluid and traditional hierarchies no longer work. “Being a leader is a transformational process that requires flexibility”, says Marina Collautti, Head of Employer Branding, Recruiting & Mobility at Generali Italy.

Today, a good boss must be “visionary and anticipate what’s coming. They must understand the effect that change has on people”. This idea points to a new culture of error, open to experimentation, as well as good communication. It’s all about creating a trusting environment for employees.

It’s not one size fits all, either. It depends on the context and there are lots of variables. That’s why we need empathetic leaders, in sync with people and their different circumstances. They need to be able to talk with them in an authentic way, able to create relationships based on listening.

As Lavinia Lenti, Direttrice HR at Sace said, “Future leaders need to be empathetic, inclusive, open to digital and innovation”. That’s why when the company trained its managers, they focused on three key principles. They were managing employees remotely, evaluating and developing employees (with a focus on gender diversity), as well as innovation, digital and data.

HR has the opportunity to work together with managers to favour engagement and motivation. It’s a chance to strengthen the leaders. “We need to value their role as a guide for their teams. Just like we care for our children, we must care for our employees”, adds Lenti. She thinks “we need more job rotations and a mix of generations and genders at the higher levels of our organizations”.

In this context, traditional training “is useless”, says Fabio Nebbia, HR Director at Coopservice. “Culture is essentially ‘knowing how to be’, or rather knowing how things are done within the company”. So to create culture, we can’t focus solely on classic training methods. “We need to consider people for all they really are. And skills correspond to measurable behaviours”.

On the other hand, work and life are no longer separated. Everything is connected within the professional sphere. Certain aspects such as flexibility and welfare are becoming more important than salaries and job titles. Nebbia believes “it’s important that managers are aware of their people’s wellbeing. They need to know the reason that they come to work each day”.

A new type of training needs to be headed up by role model leaders. ‘Managers are asked to break down stereotypes and frameworks, and to do so we need a rich culture”, says Fabio Colacicco, Group HR Director at Banca Sella. He talked about three areas to highlight: disruption, growth and freedom.

People’s complexity brings more resources, because their traits allow them to demonstrate skills that would otherwise remain hidden in the workplace. By breaking down skills into behaviours, we can discover new transferable skills in both the professional and private spheres. Self-awareness is linked to life experiences. It’s a valid substitute for traditional training. The more people find coherence in what they do, the more they behave ethically. That’s why managers need to be able to catch a hold of people’s complexity. And then treasure those precious resources.

Discover how you can boost your people’s motivation and sense of belonging

How many times do we change our minds each day? Probably less than we could do, and a lot less than we should do. We don’t change our minds because doing so is tiring. We don’t change idea because we think it means admitting that we “made mistakes” and this adds another layer of fatigue into the mix. When we have to reconsider our position, we feel guilty, as though we have missed the mark. Pyschologist Adam Grant has recently released his book “Think Again”. The author explores the idea of frequently changing your mind, even multiple times in one day.

Why are we biologically and culturally inclined to stay true to our original ideas? Physicist Carlo Rovelli explores a biological explanation in his book, Helgoland:

Most signals don’t travel through our eyes and into our brains: they travel in the opposite direction, from the brain towards our eyes. Our brains expect to see something, based on past experiences and what they know. They paint a picture of what they expect the eyes to see. The only thing that travels from the eyes to the brain is any note of discrepancies compared to what the brain is expecting.

Essentially, we go through life looking at things through the filter of what we expect to see. We’re constantly looking for confirmation that we were right – it helps our brains to save energy. Only after that are we able to receive constant signals and change perspective. It’s about changing the way we look at things. The same goes for listening and understanding our surroundings in general. It’s in our nature to champion consistency and confirm what we already know, as those things make us feel better and safer. So, biologically speaking, we’re not as inclined to look for signals that contradict the picture that we’ve already constructed. In this way, we’re quicker at managing enormous amounts of information.

From a cultural perspective, we could write at length about how our culture treats mistakes. The belief that making mistakes puts you at fault is very present, but difficult to eradicate from society. It’s very subtle. Nobody says it explicitly, but this idea of cause and effect starts when you reach school age.

But how many reasons are there behind our mistakes? How many different stories (and consequences) are there behind contradicting yourself or changing your mind? Mistakes and changing your opinion are two distinct elements in a wide spectrum of options available to us. It’s the quickest and most efficient way to learn. It’s not just about that, though. We wouldn’t be explaining the concept fully if we suggested that you must change your mind in order to learn: that would make it a simple cause and effect.

There’s much more to it than that, and nobody explains it better than the poet Walt Whitman, who famously said:

“Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself.

I am large, I contain multitudes”.

Our thoughts are so rich and we can see the world in a variety of shades. The only option we have is to constantly change our minds, enriching ourselves with the ideas of those who don’t agree with us. It’s a way of bringing another perspective into the mix.

If change was less scary, if the risk didn’t seem so great, many more things could be experienced.

It’s what anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson suggested in her book “Composing a life”. Just like Adam Grant, she suggested moving away from reasoning with only two voices – this makes us believe one voice is right and one voice is wrong. Instead, she suggested exploring every topic from three of more points of view. When we listen to more voices, we realize that they all have reasons for existing, that they are different pieces of a puzzle that together can form the richness of reality. They lighten our perception of risk when changing idea, allowing us to live many more lives.

One of the chapters in Grant’s book talks about the “joy of being wrong” and not believing in everything you think. That doesn’t mean that your thoughts aren’t worth as much if you treat them lightly: at the end of the day, every thought is worth considering. And when they are no longer needed, we can let them go.

This article was originally written by our CEO Riccarda Zezza for Alley Oop, Il Sole 24 Ore. To read the original article in Italian, click here.

The internal changes that companies have seen over the pandemic don’t just touch the professional world. They also reach into people’s private spheres. More than ever, it’s clear to see that old leadership models no longer work. We need to break down past barriers and frameworks as we try to answer new questions with kindness. Only then will we be able to unearth the wonder that this new normal can offer us.

Fatherhood can represent a new leadership model in itself. Listening, empathy, kindness and care are the soft skills and leadership behaviours used most frequently by fathers. These same characteristics form a ‘caring leadership‘ model: something that an increasing number of companies are looking for today.

But what impact do fatherhood experiences have on leadership styles? We spoke about this further at the Life Ready Conference on the 17th March 2021: The era of father leaders – New styles of leadership one year into the pandemic. Here’s what our panel of senior management and father leaders had to say.

“From the moment we find out that we’re expecting a baby, we learn to become more attentive. We’re attentive to our partners during their pregnancies, and subsequently we’re more attentive to our children. We notice their needs, their diet, their wishlist, their routines and their sleeping patterns. This feeling has been heightened through the pandemic. We’re spending more time with each other. We’re learning to focus our attention on those around us.

When a baby is born, the people surrounding them find that their identities and roles change. They find themselves in a new context. You can notice the difference even in the words they use with each other. For example, when a child becomes a brother or sister, they are no longer the person they were before the new baby arrived. We discover who we are through our different dimensions. The same thing has happened through the pandemic: we’ve had to abandon ideas of who we thought we were in order to meet other people’s needs. We’ve learned to see ourselves through our children’s eyes. We see ourselves differently and observe ourselves from a different perspective.

“When I think about what I’ve learned through my parenting experiences, the best word I can find is kindness. We are so fortunate to be able to raise human beings. But I quickly learned that they have their own characters, their own attitudes and their own ways of doing things. Rather than trying to teach my children something, I’ve discovered the importance of helping them to discover their own potential. We can try to walk alongside them, but there’s a lot that they can do themselves. We can apply that learning to work as well. If we want to bring the best out of people, we need to show kindness. It’s what makes the world go round.

We all have different roles in life. When we’re new parents, we feel like we’re our children’s heroes. We become a point of reference for them. Then, when they grow up, they discover we’re not perfect and that we have our own weaknesses. They help us to see those weaknesses too, keeping us grounded. Essentially, our children teach us how to be humble.”

“Being a parent is a gift. It puts us in contact with others that stem from ourselves. It’s like connecting with a part of your identity that’s external to yourself. Through parenting, I’ve learned to build relationships. Children need us to walk alongside them. They expect a personal relationship, with their own individual connection to us and their unique experiences. I have four children across different ages, so fatherhood for me means developing close relationships with four different people at the same time.

I’ve also learned to develop family relationships. The concept of family grows and develops over time as new people are added into the mix. Family is like a dance, it’s complex. My relationship with my child doesn’t just involve the two of us. It’s about me and my child within the context of my relationship with my partner and our wider family. So as fathers, we need to be present. We need others to know how we feel about them. Our kids need to know that they are loved. I try to tell my kids that I love them on a daily basis. It makes them feel safe and calm, even when they’re facing complex situations. We need them to know that we are there for them. It doesn’t matter how old they are – it’s super important.

When it comes to leadership, hierarchies don’t work. Leadership has to be relational and interactive. You have to make yourself available to others. Children and employees alike need to do things for themselves. But they must never feel alone. For this to happen, they need to know they can count on their manager.”

This blog is part of a series on leadership and fatherhood. Excerpts have been translated from our recent Life Ready Conference held on the 17th March 2021: The era of father leaders – New styles of leadership one year into the pandemic.

The pandemic has triggered a global transition. This transformation has dramatically added to changes that were already going on in people’s private and professional lives. Within the business context, merger and acquisition operations are transitions in themselves. There’s a thread that links all transitions together, both big and small, at work and in life: people’s need to feel listened to and to actively contribute to potential opportunities for future development. And when we talk about listening, we need to go way beyond the traditional pulse survey.

In a recent HRC event, listening emerged as one of the key ways for businesses to manage change.

While people are going through change, they navigate through a long “no man’s land”. They look at what was and what will be. In science terms, it’s called the “neutral zone”. This is the period that can really make the difference between a successful organizational culture and a prolonged period of uncertainty and confusion. When going through a transition, it all depends on how “seen” people feel.

“Listening, communication and engagement are the three factors that translate vision into purpose”, says Lea Tarchioni, Head of Pople & Organization, Italy at Enel. “Our values were born out of listening to people. They asked us to be more open and involved in change, so we developed an ‘open power’ philosophy. We need to be open to confrontation, sharing ideas and involving people across all levels in the choices we make”.

When people are going through transitions, people need to be listened to and map out their journey. Staying close to people and listening to them will boost engagement and wellbeing.

But how can we really listen to people? Focus groups dig deeper, but they can’t reach everyone. Closed questions on a pulse survey limits the richness that can emerge. These tools belong to a post-pandemic HR team. It’s not even about responding to people’s needs by creating ad hoc rooms. Rooms where you can see and listen to people to help them feel better..

Today, corporate HR management has all the knowledge and technology they need to ‘listen while’. Instead of creating new spaces where we can listen to people, we can listen while they are focusing on something else.

According to Marina Famiglietti, Head of HR at Borsa Italiana, “HR needs to really concentrate on listening to people, even if this means reaching less people than you would in a pulse survey – often people see this as a tool that the company is using to listen in on them”.

We don’t have to choose between listening to many or a few. When you really listen to people, you can do it through activities that are already engaging your people, such as through training, engagement, diversity or culture initiatives. You can listen to people through Lifeed’s digital self-reflection journeys accompanied with everything else that’s going on.

On the other hand, we are all connected. By using digital modules and open questions, we can stimulate reflection and self narration. It’s a chance to really listen to people. Listening without “making them” respond to pulse surveys that establish certain frames and bias. In this way, we can generate content that really enrich the corporate culture, but also help people feel better too.

It’s about weaving the opportunity to see and listen to people within the company. It’s about giving them a way to contribute as they work and while they form a new corporate culture. The culture forms with them as they work.

According to Fausto Fusco, HR director at BIP Group, “the company needs to understand who it wants to be and involve the corporate population. In BIP, we created new induction journeys for new hires to help them feel accompanied and listened to over the long term”.

Of course, listening doesn’t end there. “It needs to be a tool that brings specific results”, says Fabrizio Rauso, Director of People, Organization and Digital eXperience at Sogei. “The purpose needs to be ‘actionable’ and find concrete actions in people’s everyday activities”.

This emerges from business contexts that listens to and values people, enriching the collective narrative and encouraging people to contribute to creating the corporate culture and defining the purpose. In fact, Ester Cadau, International HR Audit M&A, PAI-PMI Director of Atlantic Group says it’s a “philosophical vision of human resources”.

When thinking about modern women, the question is: “What is different about women? How do they contribute to the world in a unique way?”. Women have a special legacy of caring leadership and today they have the opportunity and the responsibility to bring it to the table.

Right down to our DNA, as women we are wired around birth and care: something that’s allowed our species to survive as long as our ability to hunt. Perhaps it’s even outlived those other primal instincts.

Humans are the only species that needs caring for after birth for so long. It’s why our social skills are key to our survival.

That’s how it’s always been. It’s an extremely powerful model of caring leadership. Women can embody and diffuse it, bringing a new perspective to the world.

So what do we mean when we talk about caring leadership behaviours? Riccarda Zezza explains more in this short video of her TEDx talk in Ortygia, published on ted.com and translated into five different languages.

What is power?

If you close your eyes, and imagine power, what do you see?

asked the same question to the oracle of Google Images, and this is what I got.

Power seems to be black and white.

It’s about being strong.

Power is a puppeteer.

It’s about prevailing on others.

Power looks like a white man.

A sword is a symbol of power. With a sword, you can impose your will.

The sharper, the better.

It points to the sky: the higher, the better.

A rocket is a symbol of power.

A technological threat to lives: the logic of dominance,

empowered by progress.

Power stands out against the sky: as far as possible from the ground.

It has the shape of a sword, a rocket, a tower.

It’s solitary, it’s edgy, it’s dangerous.

The higher, the better. The bigger, the better.

Yes, power can flourish.

But it does so like a tree: if it generates life,

it is just an externality of its natural will to elevate.

Throughout the centuries, power developed

by detaching itself from the grounded things of life.

Life was intentionally life behind

so it didn’t “hold back” growth.

But why?

When did we agree that power would be about supremacy, strength and victory over others?

Did we ever have an alternative?

The oldest and longest phase of human history, the prehistorical era:

that’s when the current model of power took its roots,

in a primary instinct which kept us alive:

our capacity to hunt and fight, playing a zero-sum game with other species.

Yes, hunting was an absolute.

We couldn’t come out of it with a draw.

Men either won or lost,

it meant survival or death.

This powerful model wired man’s brain,

to the point that “fight or flight” has become its automatic response to stress.

Today, this template rules most of human activities:

in the economic arena, as in the political one,

we unconsciously apply a zero-sum game.

We compete, we fight, we either win or lose, always.

Of course!

How could we disobey such a deep and historical instinct?

And it’s a male instinct.

The reason why “Anthropos” means both “human being” and “man” is not the lack of linguists’ creativity.

There is instead a deep truth here.

For many centuries, for milennia,

the history of men overlapped with that of humanity.

Men were the creators and the storytellers.

Their instincts and attitudes shaped the world as we see it today.

The human species carries the heritage of millennia of manhood.

Today, women make up only 5 percent of the economic decision-making power in the world, despite being 50 percent of the population.

Out of 146 countries, there are only 15 female leaders

eight of whom are their country’s first woman in power.

The economic case for diversity has been recently proven,

and women have been invited to join the game, as you can see.

The doors of power are open.

Programs are teaching us how to behave in order to fit,

quotas are freeing our seats,

men are asked to make an extra effort not to follow their instinct

in selecting peers who look and behave like them.

Women have received a sort of invitation, which sounds a bit like this:

“You’re welcome to play with us: these are the rules.

Please don’t expect them to change according to your talent and inclinations.”

So, women started to join in the game:

they could wear uniforms to fit in better

and not disturb those who were there before them.

Women could learn how to run, to compete, to fight for victory.

They could even learn how to play football, and to like it!

They were entitled to change a few colours, as long as they don’t discuss the overall outfit of power, and they don’t pretend to wear a tie!

A few women got in, in a way or another:

they proved they could play the game, they could sit at the table and follow the rules.

But why so few of them?

Why, despite the clear attempts to drag women into power,

are women not getting there?

It looks like they need a damn good reason

to leave their comfortable minority seats

and they are not getting it.

I remember when I became a manager,

and the head of HR proudly told me that I could choose the best car!

I was a bit puzzled because I was not sharing his level of excitement.

In fact, I wasn’t there to get a bigger car!

This is not a detail as it may seem.

It’s the storyteller that defines who wins, and what the reward is.

And if you don’t like the reward, it might be because you didn’t write the story.

And what’s worse, this makes you less interested in writing it, also in the future.

Why should women write the definition of power?

They’ve held the minority seat for the last 5,000 years

making it possible for them to sit and complain,

leaving their hands free to fix all those little things around them that are not working.

Free not to sign contracts that they don’t like,

nor to follow uncomfortable roads.

It takes a lot of effort and motivation to aspire

to a power you don’t identify with.

Especially if the reward is a car.

Maybe good old Nietzsche was right when he said that

“In the end, things must be as they are and have always been.”

You see, the effort that our society is making is to leave things as they are,

by asking women to adapt to our current values,

such as finance, technology, competition.

Well, I hope that this effort fails, because what we have now, today,

is a unique opportunity for our species to evolve,

if women change current values, instead of being changed by them.

I believe that our call, as women, is not to join the game,

but to change the game.

Not to adapt to power, nor to replace it, but to enrich it.

Up until 3,000 years before Christ, pre-European civilizations were based on the celebration of life.

They adored a fertility goddess.

And the sociologist Riane Eisler said, they believed in linking more than in ranking.

There was no “ranking” between men and women: they completed each other, and their joint power doubled.

In these civilizations, as Merlin Stone said it, God was a woman.

The question for modern women is: what’s so different about women?

What’s the unique tribute that we can bring to the world today?

I believe that women have a special legacy, and that today we have the possibility and responsibility to bring it to power.

Women’s DNA is wired with birth and caregiving,

a characteristic that has enabled the success of our species as much as

our ability to hunt, or perhaps even more so.

For there is no other species in Nature that needs caregiving as much as ours, after birth.

And in no other species, as much as in ours, being social is a unique way to survive.

It’s always been like this.

It’s a very powerful template,

that women can embody and project,

bringing a new perspective to the world.

In the year 2000, a research professor Shelley Taylor revealed that when threatened, women don’t respond with “fight or flight”.

She wrote: From an evolutionary standpoint, women evolved as caregivers.

In the “fight or flight” model, if women fight and lose, then they are leaving an infant behind.

By the same token, it’s a lot harder to run away if you are carrying an infant and you’re not going to leave it behind.

So, how do women react when threatened? What’s their own adaptive model?

First, research found that women under stress typically spend more time tending to their children.

This tending instinct is something so rooted in women that they don’t need to be biological mothers to have it.

Second, females in times of stress also form tight social bonds, to seek out for others.

This is the so-called befriending instinct. It means that in stressful situations women forge alliances, they avoid fights, they rely on interdependencies.

That’s also women’s primary instinct.

How heavily do you see that the “fight or flight” model influences our current model of power?

How amazing would it be to enrich it with a more female, tend-and-befriend attitude?

That’s how women can contaminate power, with care and alliances.

A model that comes from an evolutionary template so close and easy to us.

How do we lay the foundations of this power, where do we learn its practices?

And especially, how can we share them with the world?I’ve got good news for you: we have everything already.

Everything at hand, everything at home.

Like all of you, I have a very engaging job. And I return home every day.

At home, my children bring me back to the grounded meaning of life.

They provide me with inspiration and reality. What’s more, they complete my deepest thoughts with the concrete details of life.

They feed my heart with the love I need to re-charge.

Being with them connects me to the high and the low, to the small and the huge, to the now and forever.

All this is impossible to leave behind, for a mother.

All this, which could be experienced by men and women alike, can reconnect power to the reality of life, giving it back the roots it’s been missing for too long.

John Stuart Mill said that “there are no absolute economic laws: the choices we make are political, and in the end they are human choices.”

So, things don’t have to be as they have always been!

If we reconnect power to life, if we bring it closer to reality, magic things will happen.

In the newspapers, we will read more about the education of our children and less about the latest results of a financial trade.

We shall stop considering it to be normal that it takes a football player a day to earn what a school teacher earns in a year.

Fan clubs will appear where people will cheer for the end of poverty,

with the same passion and energy we see today for the Champions League finals.

I can’t wait for the day we will stop considering war as an expression of power.

And start celebrating a power which is about life, again.

Bringing life back into power:

that’s how women can change the world.

This power resonates with women from the very deep roots of who we are,

calling us through our responsibility towards life,

which cannot be limited only to our households anymore.

We have to play this game.

And because we won’t adapt to it, we will make it better for everybody.

Still similar to men, and more similar to women.

We are not called to do this because it’s “fair”

and not because women “should be represented”.

This is not about helping women.

It’s about helping the world through women.

There’s a word that keeps us all on the same page, or maybe it makes us think we’re all going in the same direction. It’s “value”. Over the past 30 years people have been saying it’s at the heart of company objectives – so its people and economy are all about creating value. Then we talk about the value destination: for shareholders, clients, community, stakeholder system. We share a clear concept of value.

If we skim over the discussion over “what is” value, we know we’ve learn to measure it with a quantitative and universal measure: money. Value isn’t money, but money is a measure of it. If we think about a country’s Gross Internal Product, it would be difficult to say how it changes each year if we couldn’t measure it in euros or dollars. Imagine if we had to measure it in apples, pears, houses, health and schools! At the same time, the amount of corresponding money gives us an indicator of the “weight” something carries in terms of quality, durability, desirability and availability.

So money works as a measuring unit, in the same way that metres measure dimensions.

It simplifies things and helps us to understand each other. It helps us to exchange everything that’s material and immaterial through space and time. But over time, we’ve started to reason with each other as though money and time are the same thing. It’s understandable: money is quick and easy to measure, so why should we force ourselves to take it one step further and worry about converting figures into the essence of that value?

Let’s take the physical measurements of an object. Think about their weight – we can convert everything into a weight. Each one of us and every “equivalent” material object weighs a certain number of grams. We believe a few things about weight as well: some things are accepted as weighing more, others less so. Some things are precious because they don’t weigh a lot, others are precious because they are heavy.

You could say the same thing about dimensions: each culture has their own unwritten rules about small and large things. And we know that if we explore different parts of the world, we need to change the way we look at things (all you have to do is think about the size of a Neapolitan plate of pasta or a portion of french fries in the US). But nobody would ever think that an object corresponds exactly to their weight or dimensions: weight and dimensions are a measure, but they are not the object itself.

When did monetary measures go their own ways, becoming an absolute?

We no longer felt the need to convert it into the original value. Money was at the service of value, but when did it become the definition? We hear about people who are millionaires – “worth” more than entire countries. But what is it measuring? Somewhere we must be able to see what that number of euros “measures”: the value that really lies behind it. But it seems as though we’re unable to do so. We’ve understood the measure 7 kg, but 7 kg of what? We know that 10 kg are better than 7 kg. But 10 kg of what? What value have we decided we want to create and eventually measure with money, now that we have the technological and human ability to do so?

For example, if value is sustainability for the planet and the human race, how can we translate this into a monetary measure? There’s nothing wrong with using money to measure, but only if it’s the best measure that we have available. Bob Kennedy talked about this some time ago.

Maybe it’s time to discuss it again, making changes to the way we measure human, natural and sustainable dimensions. It’s evident that this way of measuring value is costing the system a bit too much. It’s not easy to take a step away from what we learned at school or contradict our economies. Even if that education comes from a different point of history. But today, we’re surrounded by uncertainties and we need to define what “value” means to us. Reminding ourselves that money can be a measure, but it’s not the substance.

This article was originally written by our CEO Riccarda Zezza for Alley Oop, Il Sole 24 Ore. To read the original article in Italian, click here.

We were raised to believe that it was important to have an objective or end goal, and the context surrounding it was secondary. So we looked for the love of our lives, our dream job, true friends and connections. But as we travelled down this road, we realized that each objective had a different background. They were unexpected and sometimes superficial: “weak links” that keep us company without going too deep.

Sometimes they might feel like an annoying “waste of time”, other times they can provide us with much needed relief on gloomy days. We can’t box them off because they are never a priority, like acquaintances rather than friends. We can’t control them, but they are the bread and butter of our everyday lives. That’s what we mean by “weak links”: it’s the essence of our everyday social lives, creating opportunities to stay with others.

They are generous because they don’t tie us down, but they’re also unpredictable and demanding. Right now, weak links feel like a thing of the past, and their absence weighs us down.

Over the past year, we’ve only been able to see and touch a very small circle of people. The people that are “worth” taking a risk for. We’ve tried to substitute those links with two-dimensional technology, almost trying to make up for the lack of physical contact. We’re talking about those spontaneous meetings that aren’t in your diary, the ones that underpin our relationships.

According to researcher Andrew Guydish, in the pre-covid working world, there was the opportunity to have reciprocal conversations. It allowed people to balance interactions throughout their day, not just the time spent in meetings. When people were able to do so, they felt happier and more satisfied afterwards. But this space isn’t there for us at the moment.

How many other things have we lost, along with weak links? We interviewed a few people to see what they thought – here’s what they had to say:

“I feel like I’m being deprived of life. Everything is scaled back. I don’t think about it while I’m busy at work, but when I stop, I think about it and ask myself: when will I be able to go back to normal and have friends over for a party?”

“Weak links weren’t at the centre of my life or time, but they gave me energy and made me feel like I was part of something bigger. This situation only emphasizes that“.

“I feel like a key part of my life is gone, and I feel more alone than ever“.

“I’m missing casual meetings, that time spent with friends that you don’t see much but you still love them, that small talk in work meetings with a coffee in hand… I miss spending time with others!”

“That’s what life is. It’s not just about stability or strong links. We miss life“.

We’re not missing connections because we don’t have a lot to do or are seeing a limited number of people. Just like an Italian CEO said: “I’m tired of being the boss, the husband, the father and maybe even the friend on the phone: I want to start living again, touch people, hug them, kiss them, dodge them, walk away from them. But instead I find myself here, like a hamster on its wheel”.

When we can’t see our friends and family, what happens to our identity and emotions? What happens when we can’t see those who aren’t are friends, the people that we haven’t chosen?

“Strip out the humanity, and there’s nothing but the transaction left” says Amanda Mull on The Atlantic.

She continues: “Peripheral connections tether us to the world at large; without them, people sink into the compounding sameness of closed networks. Regular interaction with people outside our inner circle “just makes us feel more like part of a community, or part of something bigger”. People on the peripheries of our lives introduce us to new ideas, new information, new opportunities, and other new people. If variety is the spice of life, these relationships are the conduit for it”.

So, was having an objective not enough? Shouldn’t we think of every action as leading to a result? Or maybe we were missing seeing or appreciating something that was key to our everyday lives, something that actually gave us humanity? Well, now we know. Now we don’t have those interactions anymore, we can see things clearly. Let’s prepare to rediscover those connections post-covid. Just like one of the people I interviewed said:

“It’s true. We have lost lots of people around us, that even if they were superficial connections, they did us some good. But we’ll find them again as soon as we take our masks off and let go of our fear. We need to find them again because we need them. Because Terenzio was right when he wrote: Homo sum, nihil humanum a me alienum puto (I’m a man, nothing that is human is alien to me). So let’s get ready to find each other again”.

This article was originally written by our CEO, Riccarda Zezza, for Alley Oop, il Sole 24 Ore. To read the original article in Italian, click here.